Saturday, December 30, 2006

Counting on abstraction

私 (me): Well, it isn't really the English itself. It's just difficult to understand new concepts. It's not like describing something concrete, like this glass or this water. I'm having to explain something you can't really experience from them, or something that only talks about what we experience -- something entirely abstract.

(Brief interrogation about the meaning of abstract.)

私: It's basically the opposite of 具体的 [concreteness].

友: But I think that has a lot to do with culture...

My friend has been veraciously studying the English language, its history and its applications. The content of her presentation (as she described it) for her university homework was something new to me, as it may well have been for her academic audience. She proposed a deep cognitive difference between our (Euro-American and East Asian) cultures concerning abstraction and perception, evidenced by the implementation in English (and other basically neighboring languages) of countable and uncountable units of measure (i.e., glasses versus water).

These Asian languages appear instead to have evolved from no such primary sense of these kinds of units but instead of shape and size, respectively evidenced by the vast number of kinds of units (i.e., 一人, the count of a person; 一台, the count of large and unwieldy objects; 一本, the count of long, cyllindrical objects, or of books; etc.). It would seem that while we (Greeks, Germans, whoever) were mesmerized by the universality of measure of different kinds of things -- how we could measure both the length of a room and a flagpole and be consistent with the unit of measurement we use -- East Asia saw difference, saw not so much the universality of strata as they did the plurality of the things they perceived. It was more important somehow that I immediately got the gist of the shape and size of what you were talking about by the way you measured it or, more directly in this case, counted it.

I know I'm in danger again of bipolarizing the cultures, the psychologies, by using adjectival opposites (and prior to that by using pronouns like 'we' and 'they'), but I'm finding it remarkable: the degree to which the Japanese are so consistently concrete in comparison to the Euro-American regions of the world. The significance of this very simple feature of difference between the two types of language has just never really dawned on me before.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

American movie

My interest, my love for my students isn't so much implicative of a fascination with the English language (though there is one), or the conservation of the methodology of its teaching, but with the ostentation of passing borderlines, of the com-passion-driven fever that accompanies diving into self-forgetting consciousness of the bizarrely foreign. It is a love for seeing past the mask of similarity, and of difference, to come to recognize that the masks cover our eyes more than they do our faces. How many fingers are there?: Eight -- but don't get too caught up in that. If all you walk away with is the conviction that there are eight, you will bypass the significance of counting in the first place; you will have mistaken the depth for the numbers, the insight for the newer point of conformity. Always look more deeply: that is the theme that I've taken from Patch's story and my current teaching experiences.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Inter-culture

I paused and thought for a moment how truly fantastic the world is. "Don't worry, my Hindu friend," I said. "There's enough Buddhist in me to keep me from doing something like that." I took the magazine and scooped the roach up and out the door.

I feel that I once misunderstood the meaning of the intercultural experience. Interculturalism takes place on every occasion of person-to-person interaction. It denotes the very process by which culture formulates and proselytizes, like moisture in the air becoming clouds. (It is to our advantage not to have a word like 'culturalism' with some disparate meaning), for interculturalism and interaction are by significance the same thing. The events that we more prominently mark 'intercultural' by habit, are those that are tinged by movements of interethnic, intersexual, or interntional currents. But these are no more culturally vital nor figuratively significant than any other -- whatever marine life might think, the sea is no less accepting of fresh water than of salt.

Still, there is something to this more highly unpredictable and eclectic sort of experience, as when last Friday evening I found myself sitting in an Indian curry restaurant after a two-hour German lesson (taught in Japanese) reflecting on whether or not my pronunciation to something I'd said in Chinese earlier that day had been adequately accurate.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

授業にの社会 -- Society in the classroom

This week's junior high is the second of three I work for, each having me for at least a week's length before I move on. Wanting to be well prepared in route, I made a special trip a couple of weeks ago to find this school. I sat on my bike in front of it at one point unsure whether or not I was in the right place (I had thought it would be an elementary school, and the sign clearly said junior high). A man, Kudo-sensei, then came out and asked in English if he could help me. I mentioned that I was the new teacher of the school (realizing I had been mistaken and was indeed in the right place), and we parted ways in good relations.

I came to discover by the beginning of this week that many of the teachers including Kudo-sensei could speak a moderate level of accurate English. (I'm afraid I've grown a bit lazy in my Japanese since, as I consider it part of my job to speak as much English with the English teachers as possible -- and that might as well include anyone else who is confident enough in their ability to push for conversation in English from me. I've also mostly kept my own Japanese ability secret from the students to encourage their own English advancement.) With that much behind him, Kudo-sensei asked the other day between my classes if I would mind attending and being interviewed in his social studies class. Simultaneously bewildered and fascinated by the idea -- what would I say? what would I be asked? in what language? -- I went for it.

In class, Kudo-sensei made the hardest of the decisions for me: he asked me to please introduce myself again -- as I had in my classes with these students before -- only this time in Japanese. Several of the students jumped, and the rest gasped, to hear conversational Japanese fall from my mouth (warning them that this was a mostly one-time event and that from here on I still strictly expected only English conversation in personal encounters with them). The present subject matter than began to emerge: the students were learning about the Japanese Constitution, and the questions more or less revolved around that. (I was also asked if I had a girlfriend; I'm afraid this comes up with almost every opportunity for question-and-answer sessions I'm granted, to which I have had to come up with a wide variation of ways to say 'no' and 'not looking.')

A girl asked how I, an American, felt about the atomic bomb of '45 -- prompted by the question of infringement on human rights. It must first be understood that human rights, jinken in Japanese, has a different meaning than what we Americans are probably accustomed to. I addressed this in my novice assessment of the Japanese Constitution, as allotted by Kudo-sensei, that cross-cultural psychology has pointed out the implicit social ties imbedded in the Japanese concept of human rights; we of Western descent are far more fluent with matters of the boundaried individual. Of the three principle rights of the Constitution -- jiyūken, or right of freedom; heitōken, right of equality; and shakaiken, social right -- the last is perhaps the most traditionally Japanese in concept of them all, if not in the matter of discrimination then in the value of import given to society and social relations. The bomb was as much -- or more really by a Japanese standard -- an infringement on the network of Japanese society (despite the legal, consitutional right had yet to be born) as on those who were physically in its radius of fire, at least as analyzed in the aftermath. I answered honestly: I would've been against the deployment of the Little Boy, especially considering the apparently true reason for deciding to use it on Japan (that is, to beat the Russians to it).

Further questions about the military came up (could I be forced to serve? did I have to kill if I did? what do I think about the principles of the Japanese military, which is meant to serve only in defense yet can attack if attacked first?). We went back and forth, in English and in Japanese, from an American then a Japanese point-of-view. Did I have any questions? I leaned forward from my chair at the front of the classroom and tapped the desk of a student I'd taken notice in my English class before, one who had a freelance manner but was, I believed, secretly reflective. Indeed, he sat looking forward, eyes clearly turned inward, at being asked what his opinion was of America's decision to end the war the way it did. After a good half-minute passed, I wasn't sure he'd answer, when he then quietly replied (in Japanese) that he felt that there are always alternatives to such measures. I tried to comprehend what had to be playing through his mind, and those of the others' in the room, in wanting to honestly answer a question that was at once of great importance yet whose response stood well possible of offending the bureacratic superior (and potential international friend) asking it. My agreement with his and others' thoughtful observations I think clarified the collective underlying pronouncement: we all want peace.

I sat through the rest of Kudo-sensei's class, taking notes in my terrible Japanese handwriting, given explanation of a term every now and then. (I am still amazed at how the topic was covered; the Japanese Constitution, at least by Kudo-sensei's curriculum, begins at least in part with a careful understanding of John Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and their influences on the American Constitution. Very little had yet to be said of Japan itself, apparently.) I felt aware of all the levels of value of this experience throughout: the gift of, finally, some sense of what it might be like to be a student member of the Japanese education system (which I have tried to imagine since my very first reflections on the country); of a Japanese point-of-view of concerning his own society and its constitutional make-up; and of a chance to be Internationalization incarnate -- an intimate foreigner in conversation and debate with my culturally significant Other. I am feeling blessed.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

裏表によって会話 -- Honest conversation

Talking with the teachers of my workplace has afforded me ideas I'd never come across before: both in general Japanese psychology and physiology. On occasion, a teacher talked with me about the instability of the tall gaijin (foreigner) stereotype. After explaining my vegetarian preferences, he expressed how much he felt meat changed the lives of the Japanese. Eras before, Japanese actually ate little meat beyond fish; now it is clearly abundant. Body types, he says, have changed accordlingly: I hold an average height for an American -- usually assumed taller than the average Japanese, which is still more or less true -- but I am yet only considerably taller than a select handfew. Japanese today are taller, bigger, and (as the menu's size options are indicating) hungrier than times before. Another ostensibly globalized effect.

On a more traditional note, another teacher, my supervisor, revealed the distinction between what is known as uraomote and honne-tatamae. The latter is similar to our characterization of 'saying one thing and doing another.' It's often felt necessary for business matters, where one must convey complete respect for their superior, even at the risk of being dishonest to or about oneself. Its negative connotation is the kind we're probably more used to: an intention or habit that contrasts the pretense. Uraomote, however, is synonymous with honesty. There are no disparate levels of saying and doing: it is singular in dimension. In a sense, the word directly antagonizes the concept of an inside and an outside, or an inside-out, and praises one who 'means what he says and says what he means.'

That even a native concept like this one inclines to reach out beyond the imaginary boundaries of culture and location, and touch those accustomed to an only slightly different gestalt, is well evident in the attempt of a gaijin, as I am, to contemplate and share it.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

もう一つの旅行 -- Another adventure

Sunday, August 27, 2006

ある最初の旅行 -- A first trip

昨日、友達の誕生日のために、一緒に松山市の道後温泉に三回以上遊びに行った。その後、呉市の行きフェリーに乗って、友達の家で揚げ物を作ったり、深夜中に中国製の映画を見たりゆっくりしていた。それでは、今日、フェリーと電車で友達と別れて、広島市に二度目に見に行った。そして、高松にまごまごに帰るにした。今の旅行では僕は有名な四国88箇所巡りの51番の石手寺に尋ねたり、広島城にも寄り道したり、色々場所まで見に行ったことができた。今、高松駅へ帰ると、新しくて狭い二室のマイホームというアパートを考えている。朝、よく見る近くの山々を隣人の屋根の上に現れる。旅行がほとんど三日しか過ぎないのに、この僕の家がもう懐かしくなっちゃったな。

Trying to life

DON'T TRY TO LIFE MORE THAN YOU ARE ABLE

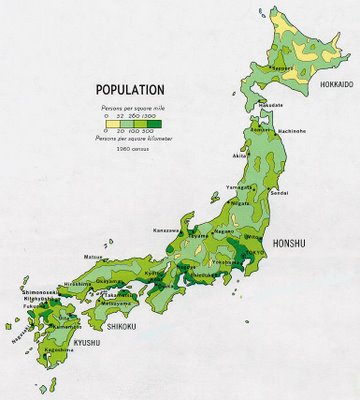

四国 - Shikoku

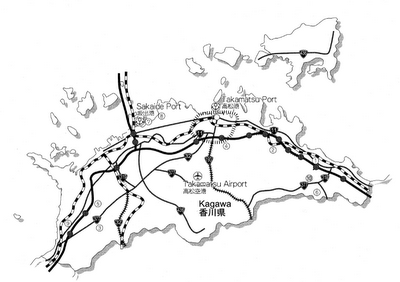

四国 - Shikoku 香川県 - Kagawa

香川県 - Kagawa 高松市 - Takamatsu

高松市 - TakamatsuPhotos from www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/japan.html, www.nikkanren.or.jp/english/shikoku.html, www.shikoku.meti.go.jp/.../industrial.html, www.bonsai-wbff.org/shimpaku/shim2.shtml, respectively.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

日本、四国、香川県、高松市

このブローグは私は外国人として旅行したり日本の生活をしたりのを公衆に伝えの目的である。JETプログラムの参加で日本に働きにきた時からイベントや話したいなことなどここに書いて入られる目的である。JETプログラムには一年間以上日本に有名なある市に置かれ、中学校で英語指導助手として教えさせてもらうことになっている。この経験についてものを伝えることに楽しみにし、よろしくお願い。